Sara Locke is an activist who was trained by the Naugatuck Valley Project. As a result of her efforts in Oxford, she was invited to serve as an alternate on the town’s Planning and Zoning Commission to advocate for affordable housing in her community.

In one of the most expensive housing markets in the country, the Naugatuck Valley Project (NVP) tackles the need for quality, affordable housing. Founded in 1983, NVP’s first success was the construction of 102 cooperative housing units. Since then, the organization has grown to include 23 congregations, labor unions, housing cooperatives, and community organizations committed to NVP’s mission of building “a broad-based organization for change that is initiated, organized, and led by low-income communities, working families, and people of color.”

Through decades of organizing and advocacy, Naugatuck Valley Project has found that successfully advocating for access to physical resources like shelter requires intangible but momentous shifts in attitude among municipal leaders. Among the challenges is a history of discriminatory housing practices such as redlining and restrictive covenants, which fueled the region’s racial wealth gap over generations. Though the most overtly racialized practices are no longer legal, NVP Director Kim McLaughlin says that over time, towns have replaced the old racist codes with zoning regulations that have the same result: a shrinking supply of affordable housing for the area’s low-income, undocumented, and Black and brown communities.

Current regulations often zone against housing options that provide additional homes within the existing residential footprint of a town. These accessory dwelling units (ADUs) can be basement conversions, additions to existing houses, or small free-standing housing units built alongside an existing house. McLaughlin says ADU’s are critical to increasing the region’s affordable housing stock.

Zoning rules in the Valley prohibit adding housing like this to your property unless you have a minimum number of acres to build on. For instance, “Watertown’s rule is six acres,” McLaughlin says. “Many cities and towns regulate how big the ADU can be and who is allowed to live in it. Most say only a family member––who proves their family connection––and that the unit cannot be used as a rental property.”

Compounding an already tight market for affordable housing, the pandemic spurred affluent people with new remote work options to relocate to the Naugatuck Valley from New York City and other locations. This has driven up rents for local families, pushing them into even more unstable housing arrangements that in turn can trigger or exacerbate a host of other problems (including domestic violence, food insecurity, mental health struggles, and school disruption).

With a $26,120 grant from Connecticut Community Foundation’s Recovery & Resilience Fund, NVP has been organizing for the local legislative change it will take to secure safe, accessible housing for Valley residents.

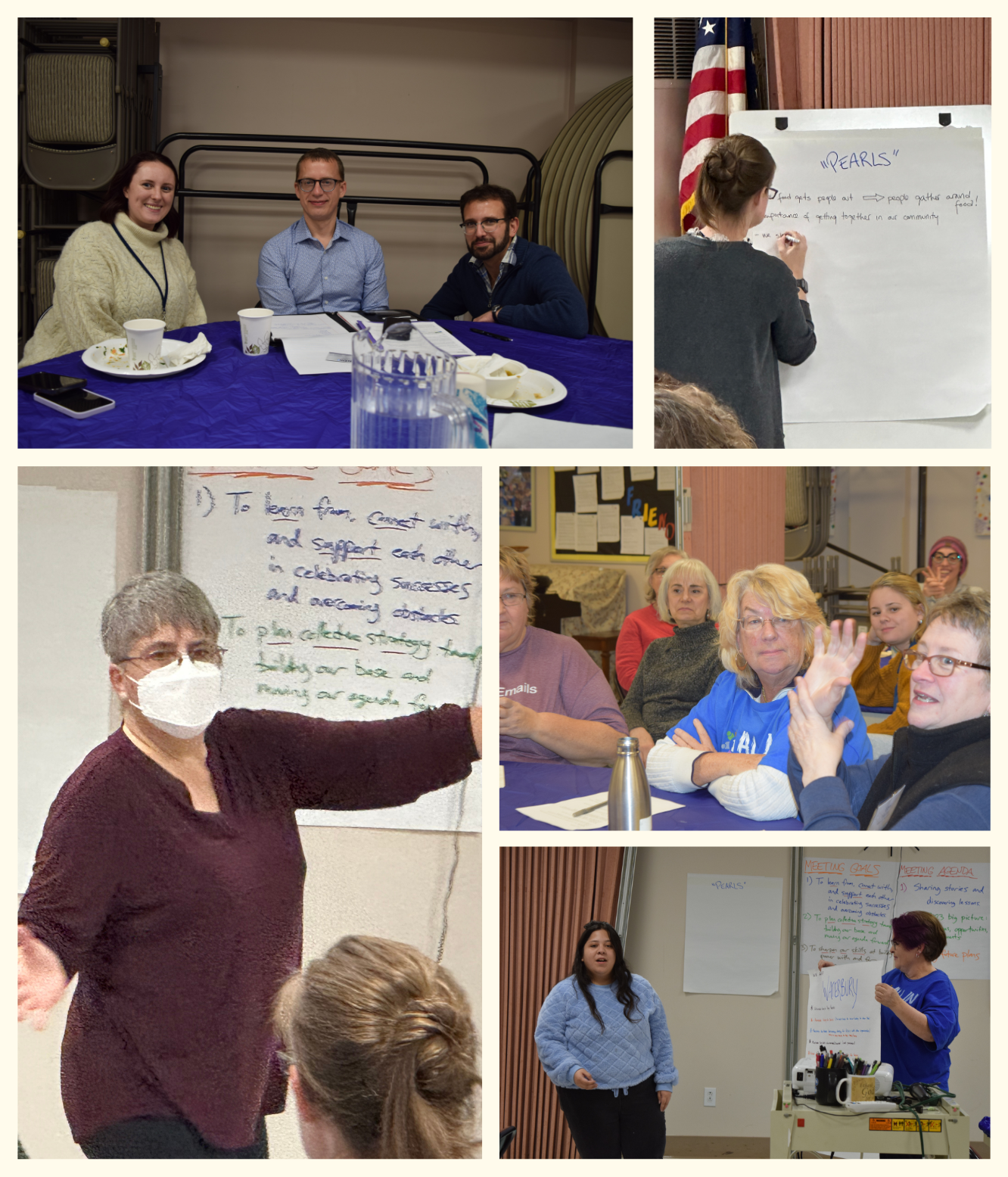

NVP used the grant to hire a staff of community organizers who developed a coalition of 72 volunteer affordable housing advocacy leaders from every town in the Naugatuck Valley. NVP organizing staff held leadership training sessions, where they taught volunteers to become agents of change in their communities. The new activist trainees learned the ins and outs of town planning and zoning commissions, how to interface most effectively with the Connecticut Department of Housing, and strategies for voicing their concerns at commission meetings and pertinent legislative hearings.

An early victory arising from this effort happened in Oxford. When the town’s first selectman announced last year that Oxford had earmarked federal grant dollars under the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) for a new police station, NVP community leaders sponsored community forums and made certain that town government heard residents’ voices regarding use of the ARPA funding. Residents pressed town leaders to instead use the funds to support the town’s housing-insecure residents and all those seeking a sense of community and belonging.

Among the NVP-trained activists who spoke up was Sara Locke, a mother of three adult children with disabilities in need of affordable, supportive housing. On the heels of her advocacy, Locke was invited to serve as an alternate on the Oxford Planning and Zoning Commission. Her appointment signals that NVP’s efforts have led to real change in the town’s political climate. Locke says regulatory bodies like the one she now serves on have historically blocked some developers’ attempts to build affordable housing.

Current zoning laws in Oxford allow residents to build accessory-dwelling units, but place many constraints and limitations on their design and use. Since Locke’s appointment, she has successfully supported community voices calling for change and the commissioners have committed to rewriting these regulations.

“None of that would have happened without the support of NVP,” Locke says. “They gave me the skills and courage to step outside my comfort zone.”

To support work that revitalizes communities and influences local systems to eliminate disparities through a gift to the Building Equitable Opportunity fund, please click here. Look here for more examples of grants like these in action.